Cavalleria rusticana & Pagliacci (Royal Opera House)

© Catherine Ashmore

Precious little redemption troubles either of these melodramas, but Damiano Michieletto achieves his own state of grace by expiating the sins of his Guillaume Tell in a pole-axingly inspired production.

His Cavalleria rusticana begins, Blood Brothers fashion, at the end. Turiddu lies dead; offstage his ghostly voice sings "O Lola ch'ai di latti la cammisa". Thus the opera's initial spine-tingle occurs before the action has even started. It's the first of many touches that breathe thrilling life into a pair of potentially half-knackered warhorses. Still to come: the processional Virgin who ignites Santuzza's sense of guilt, the ditching of pierrots and face paint, and in Pagliacci Canio's drunken nightmare wherein hallucination and reality become fatally blurred.

Mascagni's Cav has the better tunes but dramatically Pag is the hotter work. In the first, Turiddu and Alfio lock horns over a woman, Lola; his former girl friend Santuzza and mother Mamma Lucia are emotional collatoral damage. After the interval, composing contemporary Leoncavallo sends in the clowns for further testosterone-fuelled crimes passionnels. The jester, Canio, is a jealous sot who (not without reason) suspects his wife Nedda of having an affair. Have a care, woman: your husband stashes wine in his locker, and in vino verismo.

Designer Paolo Fantin's down-at-heel Italian village will have changed very little in the past two centuries, but a telltale satellite dish (and a programme note) inform us that this is the 1980s. Both operas take place on the same day, which makes the place even more dangerous than Midsomer as characters from one opera turn up in the other. Cavalleria rusticana's baker Silvio begins his courtship of Pagliacci's Nedda during his opera's famous Intermezzo; Santuzza and Mamma Lucia continue their grieving for Turiddu through the equivalent hiatus in Pag. In Cav the children are costumed for an Easter play; in Pag they perform it.

© Catherine Ashmore

Aleksanders Antonenko and Dimitri Platanias grace both operas, the tenor as Turiddu and Canio, the baritone first as his rival Alfio, then as his colleague Tonio. Platanias is in rousing form with a steady delivery that never palls despite the gruffness that's required of him. Antonenko has power and a startlingly intense identification with both his characters, however under pressure he pushes his voice beyond beauty and occasionally beyond the notes. Yet his showpiece aria, "Vesti la giubba", drips with dramatic engagement.

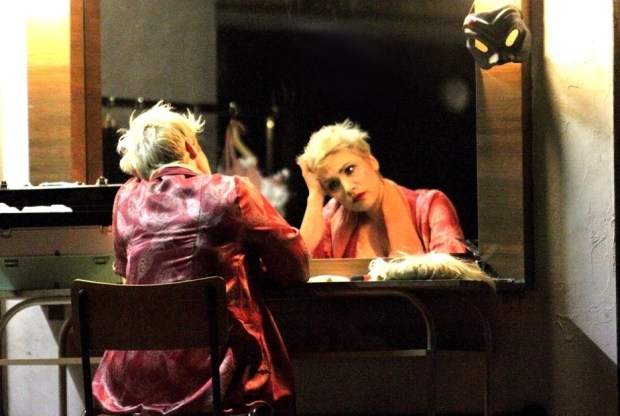

Eva-Maria Westbroek as Santuzza begins at full Wagnerian throttle, which leaves her no room for character growth over the next hour. The drama eventually catches up with her mood but it should really be the other way round. Nevertheless she suffers nobly and plumbs plangent depths with her magnificent voice. There can be no reservations about the fabulous veteran mezzo Elena Zilio, who as Mamma Lucia matches Westbroek sob for sob even when you'd rather they didn't (i.e. when the orchestra is in full flight). As for Carmen Giannattasio as Nedda, her lyrical yet sturdy instrument is an ideal fit for this repertoire and her complex physical performance is terrifically accomplished.

Other roles are superbly taken. Martina Belli (Lola), Dionysios Sourbis (Silvio) and Benjamin Hulett (Beppe) all shine, and the Royal Opera choristers excel in a pair of scores that sate them with red meat, although the company's ever-idiomatic music director Antonio Pappano will need to correct the odd ensemble lapse in due course and deal with a few bumpy moments in the orchestra.

In all, then, this bold new take on a traditional pairing makes for unforgettable theatre. Catholic notions of innocence taunt rather than haunt both operas: for all the crucifixes, illuminated Virgins and children in angel wings, Michieletto's creatures are in guilt-ridden thrall to the basest human instincts. The director's previous show may have missed the target but this one splits the apple clean in two.