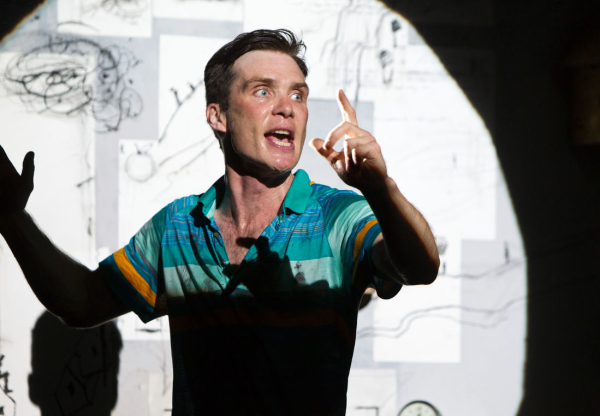

Ballyturk (NT Lyttelton)

© Patrick Redmond

It is no consolation to say that there is no consolation in Enda Walsh's first stage play in four years. The author of the libretto for the musical Once and the screenplay for Steve McQueen's Hunger is a hard act to decipher on the stage: and that's because he creates a war zone of words and feelings. There's no escape and no let-up.

After 90 minutes of frenetic babbling and athleticism from two exceptional Irish actors – Cillian Murphy (whose turn in Walsh's Misterman on this same stage last year was my personal highlight) and Mikel Murfi – pierced by the existential foreboding of a third, Stephen Rea, you leave the theatre gasping for air and heading for the bar.

All of Walsh's plays happen in real time. His unique characteristic is this immediacy and danger. The characters are numbered – 1,2, 3 – and the first two (are they brothers?) are having breakfast in underpants, rocketing around in football headgear, playing other characters out of, and off, their heads, like a crazy roll-call of Under Milk Wood.

They inhabit a fictional town called Ballyturk – a madcap, lunatic riposte to Brian Friel's fictional, poetic, becalmed Ballybeg – and other voices (those of Niall Buggy, Denise Gough, Pauline McLynn) are pressing at the walls, which are also covered in sketches between the brown cupboards and wardrobes. And there's a cuckoo clock, to mock the idea of passing time.

So, this could be Beckett as a noisy silent movie, a school for clowns, we think, but is Rea – and how moving it is to see this glorious actor, who seems to do no acting at all, return to the stage he graced in the earliest years of the National on the South Bank – Pozzo or Godot? Something of both, the duo's control and their nemesis. He appears in a cavern as the stage parts, wreathed in his own cigarette smoke. One of them must go with him, one must die.

And just as Martin McDonagh's more literal but equally brilliant plays manage to spoof Irish classics, so Walsh twists the irony knife with the unexplained appearance of a small girl, Godot's messenger, perhaps, rendered superfluous as the catastrophe of existence has been fully imagined and steps taken, no avoiding the void; Beckett's tramps only hovered on the brink. The play's a complete blast and for once I hope those words don't sound too much like a critical cop-out.