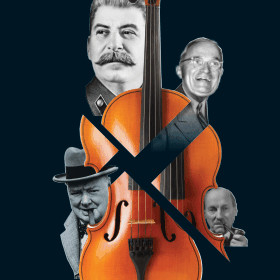

The Potsdam Quartet

Potsdam, occupied Germany, 1945. Stalin, Truman, Churchill and Atlee are in the process of restoring order to war-torn Europe: an exciting setting for a piece of theatre. The Potsdam Quartet, however, is about what happens in the room next door.

For 25 years, four men have played in one of the most celebrated string quartets of all time. They have spent the war dressed in military uniforms performing around Europe, and have now been invited to entertain the Potsdam Conference in their (apparently very regular) breaks.

The horrors of the war have little place in this room next door, where their idea of helping the war effort is knitting little squares, emasculation seeping into every stitch. Stories are told of bodies encountered in forests and lakes, but for Green the quartet and the music they create together transcends everything, so it is selfish and fatuous to worry about the war, or your family falling apart, or your unrequited love. ‘’We deal in immortal truths,” he cries in a passionate speech, ignoring the irony that our immortal truths may not always correlate. What happens in that building will decide both the future of Europe as a whole and the individual fates of the four men and their loved ones. Anthony Biggs’ direction manages to tease out the political and the personal strands of the conflict and explore how wars can take place on many differently sized battlefields.

The performances are uniformly excellent. The contrast created by Stefan Bednarczyk’s manipulative cruelty as Johnny and Philip Bird’s tremulous vulnerability as Ronnie is very poignant, particularly considering the social norms of the time. The unity of time and place emphasises the claustrophobia these men must have felt, trapped together, sharing every aspect of their lives for 25 years, but even so, the catastrophic nature of their disintegration on this particular night seems extreme. There are plenty of wry laughs to be had, but it is tragi-comic throughout, never quite shaking off the dolorous context of the event. The looming figure of the armed guard (Ged Petkunas) certainly makes sure of that.

It feels like a play in which nothing and everything happens. No one moves further than next door, and ultimately they end the play back where they started, but the excavation of the psyche which takes place in between is fascinating and enlightening. It also serves as an engaging think-piece on the various limitations of personal and political choice in truly determining how we live.