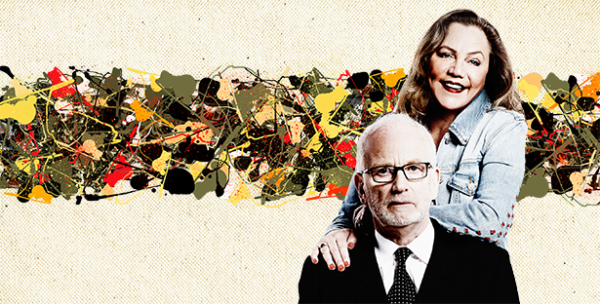

Bakersfield Mist (Duchess Theatre, West End)

© Simon Annand

Nobody does boozed-up raucousness like Kathleen Turner, returning to the London stage nine years after playing a definitive Martha in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. She appears as Maude, a slovenly, foul-mouthed ex-bartender in Stephen Sachs' formulaic two-hander: and her first words plunge you instantly into a basso imbroglio of bad bolshiness.

In truth, the play, which runs for just 85 minutes, never improves on the wild opening moments as Ian McDiarmid's prissy art expert and self-appointed fake-buster, Lionel, survives a brute welcome from a pack of wild dogs out in the Californian trailer park, flounces into Maude's mayhem and promptly declares that her three-dollar junk sale painting's not a Pollock.

Still, Polly Teale's production does then forge a series of tart, bruising, often funny exchanges on the meaning of art, the value of informed expertise ("My opinion means something, yours doesn't," snaps Lionel, standing up for critics) and the volcanic spirit of true creativity.

Lionel likens Jackson Pollock's action paintings to the splitting of the atom, dancing his technique of random ejaculations like a man possessed. Lionel, you might say, has loosened up, and McDiarmid manages to paint his unlikely bourbon-fuelled explosion into a startling stage picture.

As in Yasmina Reza's Art, the painting (which we never see) is a catalyst in a relationship. Reza's play was about friendship, this one about an unlikely meeting of minds: Turner's outlandishly blowzy hostess goading McDiarmid's increasingly unguarded art guardian – he's an ex-director of the Metropolitan Museum and a teacher at Princeton – into the confessional box. It’s not a pretty sight.

A seemingly authentic validation of the painting places the conclusion in jeopardy, but a story that sounds "real" places the whole play in the context of evaluation and consumerism in art: the virtuoso violinist Joshua Bell played Bach on the subway and nobody cared or even noticed. But hey, you walk past a Hawksmoor church each day in London and do you ever look at it? Does that mean you don’t care?

At this level of argument, the play is full of ideas and provocations. It's less convincing when it sags into physical violence and critical aggression. The characters can't possibly know each other well enough to carry on like neighbours in an Albee play, or worse. But it's great to see Turner still careering down an untended path of soggy emotional wipe-out, and McDiarmid bristling inimitably like a porcupine before being trampled underfoot by a gorgon.