King Lear (Cockpit Theatre)

© Robert Workman

At the last preview of Darker Purpose Theatre’s King Lear at the Cockpit, David Ryall was reading the title role, but nobody asked for their money back. This great watery-eyed stalwart of the National Theatre during the Olivier and Peter Hall years has lately completed a course of chemotherapy that has enfeebled his memory and powers of concentration.

But Ryall reading the telephone directory would be worth seeing, and there are moments when he goes off-book and suddenly pierces to the heart of the play – "Who is it who can tell me who I am?"; holding Goneril’s stomach while delivering the sterility curse; offering a piece of toasted cheese to the imaginary mouse – that move you infinitely more than does Simon Russell Beale‘s glinting, super-rational National performance.

The other thing is that Ryall’s own daughters are cast in Lewis Reynolds’ well organised if unexciting production, which is played under a canopy of five large grey banners that tremble in the storm scenes: young Charlie Ryall as a steadfast, attentive Cordelia, and her elder sister, Imogen Ryall, a jazz singer, as the doctor in the last act.

They’re onstage carers of their own dad who, though 79 years old (nearly Lear’s four score and upward), and wispy-haired, is strong of voice and naturally commanding, even when sprawling on the floor and searching out the next cue with a musical hum.

Ryall’s last stage performance was Feste in Peter Hall’s disappointing NT return with Twelfth Night and this, for all its bumps and hiccups, is a much better valedictory, gathering force in the second, more lyrical half of the play. The storm and hovel scenes are not a highlight; Ryan Wichert‘s cap-and-bells Fool is extremely trying, whereas the military and adulterous manoeuvres of a superciliously upright Edmund (Michael Luke Walsh) and Lear’s literally unnatural daughters seem to presage a new political era of loose morality and clamp down.

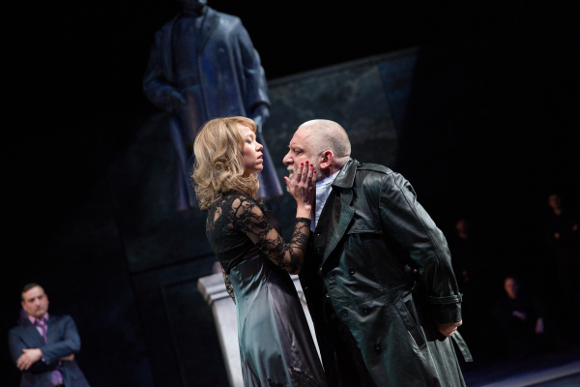

Goneril is particularly well done by the too-little-seen Wendy Morgan (she starred in John Schlesinger’s Yanks and Hall’s NT company alongside Ryall in Animal Farm, and in Martine), a blonde and lubricious watchful bombshell in contrast to the stock pinched acidity of Nikki Leigh Scott‘s Regan.

The other notable performance is Dominic Kelly‘s Edgar, begrimed in mud and wearing an extravagant loincloth of soiled bandages as the supposed madman Poor Tom, just as moved by his own discoveries as is the starker, stranger Tom Brooke at the NT; his scene on the cliff with his own father Gloucester (a somewhat fussy reading by Stephen Christos) hits home hard, and there’s a shocking innovation when he literally punches Oswald (a sexually ambiguous Anna Hawkes) to death.

Ryall enters the first scene, wearing a grey greatcoat and spectacles, clutching the script, in a wheelchair. At the end, he’s put Cordelia in that same wheelchair and dies in her lap, letting the script drop to the floor. Like Prospero, he drowns his book, discards his knowledge, and passes on unencumbered by the play or his own struggle. It’s a powerful and original coda to a performance that you’ll be glad to have seen, even if only in outline.