Matt Trueman: The shows you wish you could see again

© Greg Goodale

Though I knew of its form, its guest performer and its theatrical trickery, and what all that meant for theatre, I had no idea about its feeling or what it was like to watch it. An Oak Tree, for me, was a chapter in a textbook or a notch in theatre history. I didn't realise how well the play caught grief or the sadness I'd feel sitting alongside its daughterless father. Nor had I clocked how funny it could be, how silly and serious at the same time. All that came as a surprise.

Theatre's emphemerality is one of the very best things about the artform. I think we watch it differently as a result, knowing that we've got one shot and so trying, somehow, to hold on to a show as it disappears. Half an hour into London Road, having just worked out what I was watching and how to watch it, I remember wishing that I could go back to the start. Too late. It's gone.

An Oak Tree has that coded into its DNA. Since it uses an unrehearsed guest performer, every show is a complete one-off. That's what makes this anniversary revival at the National Theatre possible: Crouch can revive the very same show now, ten years later, precisely because An Oak Tree is completely unique each time. If you tried to revive The History Boys as it was then, you'd fall at the first hurdle. Richard Griffiths is sadly no longer with us, and Mssrs Cooper, Corden and Tovey – superstars all – could never convince in school uniform.

When we talk of revivals, we usually mean something else: an all-new production of an old play, created from scratch with new designs and new performances. When Trevor Nunn revives The Wars of the Roses in the autumn, it will be entirely new, even though that playscript seems inextricably bound up with Peter Hall's original production – a staging so seminal that no-one's thought to (or dared) revive the play in half a century.

There are, however, exceptions and gradations. Have a look in any old Samuel French playtext and you'll find a floor map to replicate the layout – if not the decor – of the original design: drinks trolley goes here; French windows, there. If we'd dub that a new show, a West End long-runner can go through any number of cast changes and still be the same. In theory, that should fundamentally change it, but in practice, a new actor often steps into a fixed role and hits all the same beats. Perhaps such shows gradually decay like old photographs. They become copies of copies of copies.

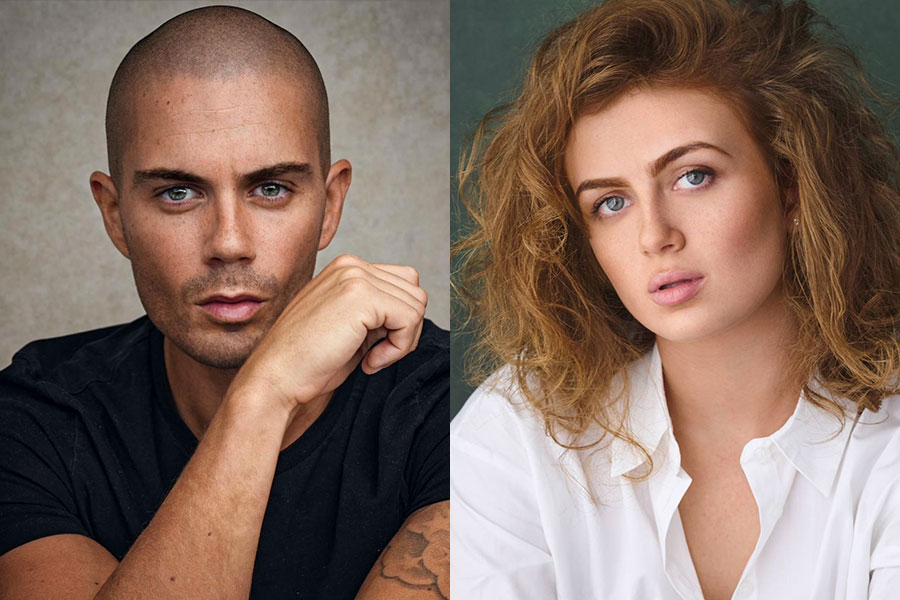

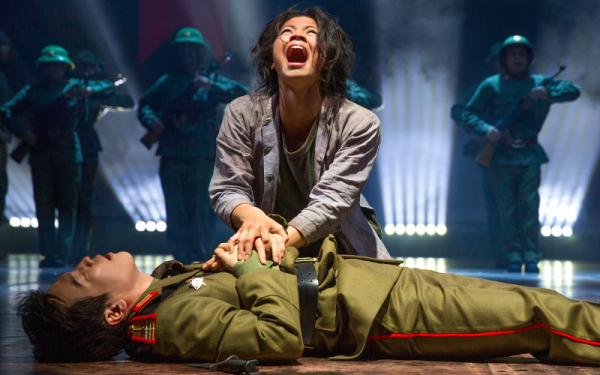

That 'sameness' can be a selling point. Miss Saigon was revived last year in its original form, only brushed up with new technology and stagecraft – the equivalent, perhaps, of digitally remastering a classic album or a film. Likewise, the return of Cats was one revolving stage short of a replica. Watching it, 20-plus years later, was a strange, echoey experience: absolutely familiar and yet completely revelatory. 'This is Cats?' I thought, as a chorus of tap-dancing, binbag cockroaches with sieves for eyes burst out of an oven. Nor had I quite expected the daring and dazzle of Gillian Lynne's choreography.

© Matthew Murphy

On Saturday, I went to the Royal Opera House for the first time to see its production of La traviata. Revived for six weeks this summer, and totally new to me, Richard Eyre's production has been playing, on and off, since 1994. New cast members step in every so often, but otherwise it might as well be preserved in aspic: the same set, the same costumes, the same blocking. Next month's La bohème dates back to 1974. ROH's storage costs must be astronomical.

Something similar happens in the European rep system. At the Schabühne in Berlin, Lars Eidinger has been playing Hamlet for the last seven years. He was 32 when he started and in January, he'll turn 40 – older, even, than David Tennant's mature student prince for the RSC. All these productions still sell well: short runs, packed houses. Toneelgroep Amsterdam, Ivo van Hove's company, brings its best shows back on occasion, usually around international demand.

'It seems five or six years needs to pass before you can start craving a show'

There are benefits to that: last year, I very nearly travelled all the way to Adelaide just to catch up on The Roman Tragedies. Having missed its Barbican outing in 2009, I've been cursing my stupidity ever since. The chance to catch up at some stage in Amsterdam – and there are whispers of the Barbican bringing it back – is a great thing. With other shows, I know I'll never get the chance: last week, someone was explaining the power of Nicholas Hytner's Carousel, how it changed the nature of musical theatre in Britain. I'd give anything to have seen Nicol Williamson onstage. Ditto Donald Sinden's Malvolio and Michael Gambon's Eddie Carbone. Instead, I have to be content with recordings and criticism – a start, but no substitute.

It's not all about catching up though. Some shows I wish I could see all over again: Mike Bartlett's Cock with its original Ben Whishaw, Andrew Scott, Katherine Parkinson cast; Earthquakes in London on that winding red catwalk, booming out (ha) Coldplay, Arcade Fire and Marina and the Diamonds. Would they feel dated today or would they zip and zing as they did at the time? Timing's all important: I don't yet feel the same about other shows that I've loved, Three Kingdoms, say, or A View from the Bridge. It seems five or six years needs to pass before you can start craving a show.

Returning to shows like this can be remarkable. When Mark Rylance stepped back into Olivia's corset in the Globe's all-male Twelfth Night, it held special resonance for me. In 2002, aged 17, it was one of the very first shows to get me hooked on theatregoing. What was so fascinating about its return was noticing how much I'd either missed or forgotten. While the shows inevitably change – actors age and resonances shift – so do we. Theatre reflects that back at us, beautifully.