Matt Trueman: theatre needs to work at a way of using the camera

The camera has become ubiquitous. Almost all of us carry around a miniature television studio in our pockets. We snap and selfie, Instagram and Periscope. We live life through a lens. Almost every live event has some kind of mediatised element. Music gigs and sports matches loop back on themselves via big screen. Theatre, as so often, is lagging behind.

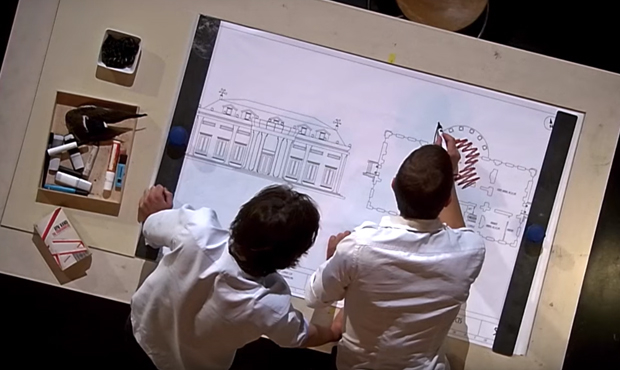

Last weekend, I saw Ivo Van Hove‘s staging of The Fountainhead, Ayn Rand’s cracker-dry novel about individualism and architecture, in Antwerp. Aside from the sheer gumption of staging a 700-page book about buildings, the most impressive thing was Van Hove’s use of cameras. His designers Jan Versweyveld and Tal Yarden (video) studded the set with cameras – many of them peering down from the ceiling, offering a birds eye view.

The result was a complex, layered piece of theatre – one that offered multiple perspectives at once. (The trailer gives a sense of it.) You could have a scene playing out onstage, while another appeared onscreen. Real-time actions could be refracted and distorted. Behind the plot was a constant sense of work: fingers rattling away at a typewriter or an architectural plan coming together on paper. Objects were enlarged: a printing press whirred away, a coffee going cold. Sometimes, the screen carried or extended the narrative: as news of a major explosion breaks, Dominique Frankcon lies on a table, bleeding profusely and staring up at the sky.

Not only did cameras allow a vast, tangled story to play out onstage, condensing pages of dry description down to a series of images and allowing several events to take place simultaneously, it also disrupts the way we watch. There’s a brilliant sense of composition, full of juxtapositions and tensions – beauty smashed against ugliness, love against work, human against machine. Your brain takes in two things at once, sometimes more. It feels like a modern mode of watching: theatre in split-screen or multiple tabs.

The roots, of course, go back to Brecht and his montage effect, aiming to "connect dissimilars in such a way as to shock people into new recognitions and understandings." The German had to make do with simultaneous scenes on a single stage. Van Hove, however, is able to establish different layers of reality and materiality. His vocabulary is far more sophisticated.

We have, in this country, gotten better at integrating video design into the theatre. Video mapping has taken projection to new heights and recorded images regularly take on some of the storytelling. Finn Ross’s videos create most of the locations in Curious Incident, while, as far back as 2005, The History Boys relied on video to deal with some scenes – shots of Hector on his scooter, in particular.

However, when it comes to using cameras and live feeds, we remain incessantly literal. Where we use cameras onstage, chances are we’re invoking broadcast media: politicians addressing their nation, news reporters talking to camera. We get CCTV footage and webcam chats, but the camera’s presence is usually explained. It’s part of the story. Even something as contemporary as the Almeida’s Oresteia was fairly conventional in its use of cameras.

There are a couple of exceptions. Joe Hill-Gibbins has been developing a vocabulary of his own using cameras and live feeds. In Edward II, he disrupted the theatre space by playing scenes on the National’s roof or in the Olivier’s wings, and his recent Measure for Measure at the Young Vic created the imagery of hip-hop videos and televised dawn raids. Jeff James too, who has worked with Van Hove, used the language of cinema in La Musica, placing his two actors in extreme close-up that we might catch every tiny flicker of emotion on their faces. You could also point to the meticulous televisual trickery of Katie Mitchell‘s camera shows, such as Waves or, more recently, Fraulein Julie, and the special effects wizardry of Complicite in Master and the Margarita.

By and large, though, the camera is used simplistically – largely as part of a narrative, not as a means of telling or interrogating it. The reason, most likely, is that video is technologically complex, and live video, doubly so. Making it an integral element of storytelling means building it in from the very start of a process and, as it stands, given six week rehearsal periods and short tech try-outs, our theatre ecology isn’t set up for that.

Equally, though, we can’t afford to ignore it. The camera is a staple of the way we see the world, and theatre, being a composite, mixed-media artform, needs to work at a way of using it. The results will be complex and contemporary, in tune with the world offstage, not one step behind.