Why aren't there more revivals of new British plays?

Is Jez Butterworth‘s Jerusalem the best play of the 21st century so far? I think it is. All the time I was watching The Ferryman, I was thinking ‘this is all very well but it isn’t a patch on Jerusalem.’

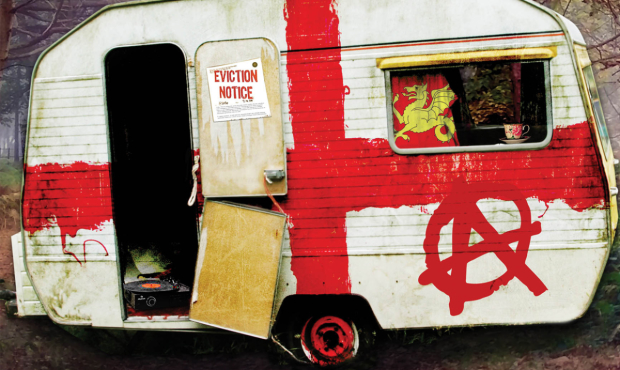

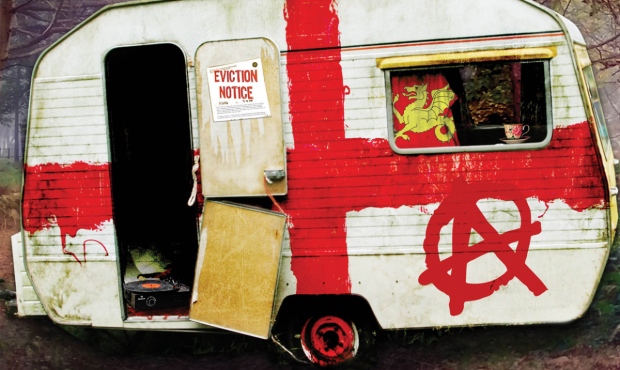

Yet I have had no chance to test that sense of the play’s importance. I saw it three times after it appeared at the Royal Court in 2009, and felt the play said something important, eternal and premonitory about the English and their attitudes. That in its portrayal of Johnny ‘Rooster’ Byron, eternal outsider, but keeper of a mythical defiant flame, it caught something of a longing for something forgotten that the vote for Brexit revealed on a wider and more vicious stage. That the sheer heft and thrust of Butterworth’s language, at once realistic, comic and poetic, was simply one of the finest bits of writing I have ever sat in a theatre and enjoyed. That it was a work of genius.

But I haven’t had the chance to test out those impressions in a theatre since 2011 because after its initial production, with a mesmeric central performance by Mark Rylance, and equally impactful ones from the supporting cast led by Mackenzie Crook, I haven’t been able to see it. It came, conquered London and Broadway and then vanished – apart from a revival in San Francisco, and a tour by local performers in Devon and Cornwall in 2014.

The passage of even a few years can profoundly affect how a play comes across

Which is why it is so thrilling that the enterprising Watermill Theatre in Newbury is mounting the first major revival of Jerusalem, directed by Lisa Blair, as part of its spring season next year. Casting is eagerly awaited, but with all due respect to Rylance and the others, the play is the thing. If it is as good and vital as I think it is, it will thrive and blossom in its new incarnation.

Certainly it will be interesting to see; the passage of even a few years can profoundly affect how a play comes across. I felt very strongly, for example, that Lyndsey Turner’s revival of The Treatment at the Almeida this year revealed Martin Crimp’s 1993 play in a new light and with pressing relevance. Whereas Joe Penhall’s Blue/Orange from 2000 felt less robust in last year’s Young Vic incarnation.

We regularly revive the Pinters and the Becketts – but we lose track of the exceptional writing that flutters into brief life in London

Plays need to be performed to worm their way into the national consciousness. It is all very well setting Jerusalem as an A-level text – my son studied it – but it is even better if students can see the production as well as read the words on the page. It strikes me that one problem in contemporary theatre is that really good new plays struggle to find a second production and so become recognised as the classics they are.

Sometimes this is down to chance. A transfer of Nina Raine’s excellent Consent, which debuted at the National Theatre earlier this year, was planned but fell through thanks to circumstances beyond anyone’s control. But I’d love to see plays such as Lucy Kirkwood’s The Children and Mosquitoes (two terrific works from a writer at the top of her game) going into much wider circulation. And why has Chimerica (another play now studied at A-level) never had a regional tour? How would David Eldridge’s In Basildon (2012) stand up to scrutiny five years later?

And there are exceptions. The Donmar, for example, is bringing back Peter Gill’s The York Realist, which premiered in 2002. But the general danger is that we regularly revive the plays of the 20th century masters – the Pinters, the Becketts, the Hares, the Albees – but we lose track of the exceptional writing that flutters into brief and vivid life in London and then is lost for years. It means that audiences outside London are often deprived of seeing the best of new writing, and that children studying these things think they exist only in books not in the world. The Watermill is beating a path that I hope others will quickly tread.