What happened when August Strindberg believed he could make gold

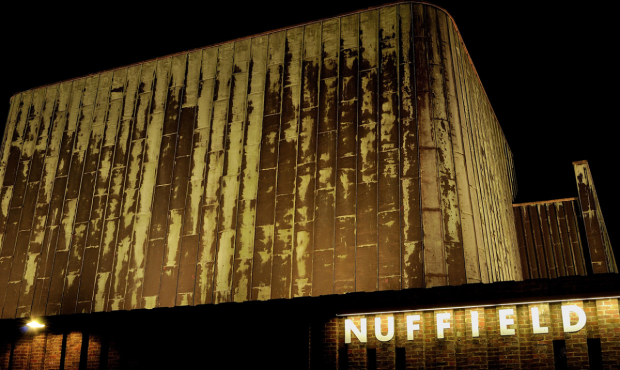

© Creative Commons

Why, in Paris in February 1896, did August Strindberg suddenly announce to his startled friends – and enemies – that he was giving up playwriting to become an alchemist? The Parisian theatre had been good to him: in 1893 a revival of Miss Julie had been a great success and in 1895 The Father was rapturously received. At last he had international fame, he was seen as the equal of his bitter rival, Ibsen, and by some as his better (something I’d agree with, though Ibsen vs Strindberg is a can of worms of a debate!).

But here he was, holed up in a cheap hotel, The Orfila in the Rue d’Assas, his hands burnt by chemicals, trying to make gold. He wrote the experience up in his novel Inferno. Like so much of his autobiographical writing it is unreliable. The brighter and the more dramatic a story about an incident in his past, the more Strindberg convinced himself it was a true memory.

He was convinced supernatural forces were trying to stop his experiments

But it is beyond doubt that he was in the midst of a psychotic episode: he was convinced supernatural forces were trying to stop his experiments; a man in the room next door was beaming electricity at him; the 'forces' were trying to gas him through the wall; he feared they would send a woman succubus to seduce him and drain his blood.

You can say there were causes. In 1884 he was prosecuted for blasphemy. Against her wishes – one of their three children was ill – he left his first wife Siri in Switzerland and returned to Stockholm to defend himself. It was serious: he was taking on the Swedish state and faced a two year prison sentence. He won but left Sweden enraged by the cowardly lack of support from socialist and feminist intellectuals. In a violent reaction he lashed out at the progressive causes he had once championed. In the next ten years the great naturalist plays came but the trial had snapped something within him. His marriage disintegrated. In Berlin he became part of a glamourously poisonous arts scene around a café, The Ferkel, where he met the brilliant, perhaps equally unstable, Frida Uhl. Their tempestuous marriage lasted two years. So by 1896, drinking heavily, which in Paris meant absinthe, he was sliding towards his ‘inferno period’. And the bottom of the pit was the room in the Hotel Orfila.

His alchemy was a way out of a massive writer’s block

But look again. Like all mystical systems alchemy is a process of steps towards a state of perfection. First everything must be broken down in the stage of 'putrefaction'. Only then can the ascent to the final stage begin, 'coagulation': the transformation of all that is base into incorruptible gold. But – and this greatly appealed to Strindberg – to achieve the chemical process the alchemist must, in parallel, break down his own very being to be able to ascend to a final state of realisation. Alchemy is a moral quest.

© Catherine Ashmore

And what was the quest? A way out of a massive writer’s block. He had taken naturalism as far he could. Instinctively, despite the psychosis and the absinthe, he knew that to write again he had to destroy then rebuild his view of the world. And it worked. After four years silence Strindberg returned to the theatre writing a completely different kind of play like A Dream Play, The Ghost Sonata and To Damascus, staging psychological states so vividly you think you are dreaming wide awake.

So alchemy and playwriting were part of the same project. By ‘naturalist’ or ‘expressionist’ means he wanted audiences to see the world in a new light, illuminating our dark secrets.

By Howard Brenton

The Blinding Light runs at Jermyn Street Theatre until 14 October.