Michael Coveney: Ayckbourn's friend Resnais dies, Callow's Shakespeare returns, ENO’s Rodelinda rules

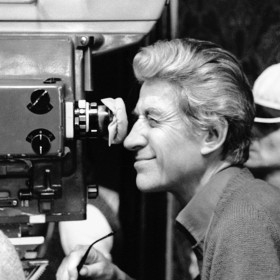

The great French film director, Alain Resnais, who died on Saturday aged 91, is best known for Hiroshima Mon Amour and, especially, Last Year at Marienbad, one of the most beguiling and mysterious European films of the last century. But he also had a special relationship with the British theatre, mostly through his friendship with Alan Ayckbourn.

Resnais was a regular in the audience at the Stephen Joseph Theatre in Scarborough for many summers before the two Alans got to know each other. Alain married his second wife, actress Sabine Azema, in the Yorskshire seaside town, and Alan and his wife, Heather Stoney, were witnesses. More than that, Ayckbourn wrote a role specifically for Sabine in his interconnecting plays House and Garden, and she appeared in them at Scarborough (Zabou Breitman took over at the National Theatre).

Friendship led to three collaborations on film: Smoking/No Smoking (2003), based on Intimate Exchanges; Hearts (2006), based on Private Fears in Public Places; and the director's last film, premiered to mixed reaction at last month's Berlin Film Festival, Life of Riley.

These were all French films, but Resnais is also celebrated for one of the finest English language movies of the 1970s, Providence, in which John Gielgud played a dying alcoholic novelist surrounded by friends and family (who included Dirk Bogarde, Ellen Burstyn and David Warner) in a script by playwright David Mercer.

It is extraordinary how Gielgud, a totemic figure of the British stage, participated in so many ground-breaking projects, not least Providence, or Peter Greenaway's Prospero's Books (in which he spoke every line of The Tempest himself), or Alan Bennett's Forty Years On or indeed Edward Bond's Bingo.

In the latter, he played Shakespeare, dying and in despair, and was concerned that he didn't really understand, or indeed like, the play. He was, in any case, magnificent in it. By temperament, he preferred the notion of Shakespeare the great poetic artist to Bond's portrait of Shakespeare the capitalist landowner, and projected that preference for many years in his globe-trotting solo show, The Ages of Man.

In his autobiographical collection of essays, My Life in Pieces, Simon Callow recalls a performance he gave of all 154 sonnets of Shakespeare in a packed-out Olivier auditorium at the National "in which Sir John rather prominently sat, scaring the life out of me."

Gielgud is long gone and poses no further threat to Simon's onstage equilibrium, but he must linger still in the back of his mind, especially when performing – as he is for just two more weeks in an impromptu gig at the Harold Pinter – his excellent Being Shakespeare, not least because the structure of Jonathan Bate's play – more a compilation with deft biographical links – is built around the seven ages of man speech from As You Like It, Gielgud's identical territory.

But it's a very different sort of show, not at all mystical or high-flown, and still as compelling as it was when last seen in London, three years ago, at the Trafalgar Studios. Who'd have thought ever to see Simon play the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet, let alone as, well, alone? It's almost as bizarre, and revealing, as Eileen Atkins playing a solo version of the reconciliation of Lear and Cordelia, as she did recently in the candlelit Sam Wanamaker Playhouse.

Callow is not telling the story of Shakespeare's life, exactly, nor does he indulge in speculation of any kind (on authorship, the missing years, spying activities), but he does infuse the speeches with an idea of Shakespeare's experience in matters of the heart, of practical citizenship, marriage at an unusually young age (just 18) to an older woman, the loss of a child.

It's immensely affecting, and Callow's delivery is informed with grace and appreciation, and minimal bombast. I even warm now to his Falstaff (which is more than I did when he played it, twice, in full productions) in the "honour" speech, and there's a tremendous version of Sir Thomas More's speech to the mob in the disputed play, and a shivery evocation of the Forest of Arden to the north of Stratford-upon-Avon, a place of motorway roundabouts and Little Chefs these days.

But for unadulterated sublimity this weekend you had to be at the Colisem for Richard Jones' ENO revival (a joint production with the Bolshoi in Moscow) of Handel's Rodelinda, done as a volatile dictatorship cartoon melodrama with the most wonderful second act of music imaginable, absolutely rigorous and transcendent at the same time.

In a new translation by Amanda Holden, Jones and designer Jeremy Herbert create a nightmare power struggle of closed cells, blunt instruments, grim torture – made even more tortuous by the serpentine lines of the plangently melodic music – surveillance, betrayal and tattoos. Unbelievable singing by counter-tenor Iestyn Davies as the usurped tyrant and Rebecca Evans as his valiant Fidelio-like wife of the title, and glorious accompaniment (including two harpsichords) conducted by Christian Curnyn.

In my book, that makes three hits in a row this year for the ENO, following Peter Grimes and Rigoletto, and I've enjoyed the music so much at all three that I've no doubt rationalised in my mind some of the excesses and perversities itemised by the experts. But that's fine by me. Bottom line is: ENO is serving up great theatre at the moment, the best in town.

For more on opera, visit Whatsonstage.com/Opera